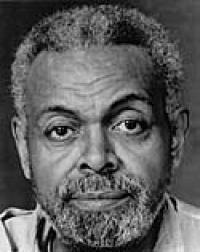

American dramatist, poet and novelist, who has explored the experience and anger of African-Americans. Baraka’s writings have been his weapon against racism and later to advocate scientific socialism. Having been converted to the Kewaida sect of the Muslim faith, he assumed the name Imamu Amiri Baraka.

American dramatist, poet and novelist, who has explored the experience and anger of African-Americans. Baraka’s writings have been his weapon against racism and later to advocate scientific socialism. Having been converted to the Kewaida sect of the Muslim faith, he assumed the name Imamu Amiri Baraka.

Let me sit and go blind in my dreaming

and be that dream in purpose and device.

A fantasy of defeat, a strong strong man

older, but no wiser that the defect of love.

(from ‘The New World,’ 1969)

Amiri Baraka was born in Newark, New Jersey, 1934, where his father worked as a postman and lift operator. He studied at Rutgers, Columbia, and Howard Universities, leaving without a degree, and at the New School for Social Research. His major fields of study were philosophy and religion. Baraka also served three years in the U.S. Air Force as a gunner. Baraka continued his studies of comparative literature at Columbia University. He has taught at a number of universities, including the State University of New York at Buffalo.

In 1956 Baraka began his career as a writer, activist, and advocate of black culture and political power. In 1958 he founded Totem Press. In Harlem he established the Black Arts Repertory Theatre, which presented poetry readings, concerts, and produced a number of plays. The theatre was disbanded in 1966 and Baraka set up in Newark the Spirit House, a black community theatre (also known as the Heckalu Community Centre). In 1968 Baraka founded the Black Community Development and Defense Organization. He has also been Secretary-General of the National Black Political Assembly and Chairman of the Congress of African People.

“I am soul in the world: in

the world of my soul the whirled

light from the day

the sacked land

of my father.”

(from ‘The Invention of Comics’)

Baraka’s first published work was a play, A GOOD GIRL IS HARD TO FIND (1958). In 1961 appeared PREFACE TO A TWENTY VOLUME SUICIDE NOTE, a book of verse with personal and domestic poems. The book was published in an underground series that included work by Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac. Several other collections followed, among them THE DEAD LECTURER (1964), BLACK ART (1966), BLACK MAGIC (1969). His later collections include IT’S NATION TIME (1970) SPIRIT REACH (1972), HARD FACTS (1977), AM/TRAK (1979), THOUGHTS FOR YOU! (1984).

In 1965 Baraka divorced Hettie Cohen, his Jewish wife whom he had married in a Buddhist temple in New York in 1958. They edited in the late 1950s the Yugen magazine which published poetry – Hettie did the pasting up and collating on the kitchen table. Later she specialized in children’s books dealing with black and Native American themes. She has depicted her life with LeRoi Jones in her book of memoir, How I Became Hettie Jones (1990). In 1966 Baraka married a black woman, Sylvia Robinson (later to be called Amina Baraka); they had five children. In 1967 he helped organize a National Black Power Conference and next year he left behind his ‘slave name’, Jones, for a new African identity, Imamu (Swahili, for spiritual leader) Amiri Baraka. With his own conversion to Marxism, Baraka dropped ‘Imamu’ from his name as having ‘bourgeois nationalist’ implications.

In the 1960s Baraka’s works became progressively more radical and involved with issues of racial and national identity.

“We must eliminate the white man before we can draw a free breath on this planet,” he once stated. In his early poems Baraka dealt with such subjects as death, suicide and self-hatred, but his view took a new turn and he focused on the separation of the races and political activism. After 1974 his political ideology underwent a change. He abandoned Black Nationalism and embraced Marxist Leninism, supporting the revolutionary overthrow of capitalist system, black or white. As an opponent of the middle-classes, Baraka has criticized among others the likes of James Baldwin to be too ‘hip’. Baraka’s Marxist-Leninist poetry, such as HARD FACTS (1976), is well-crafted and includes some of his best-written work.

Baraka was a teacher at the New School for Social Research, New York (1961-64), a visiting professor at San Francisco State College (1966-67), Yale University, New Haven (1977-78), and George Washington University, Washington, D.C. (1978-79). He was an assistant professor (1980-82), an associate professor (1983-84), and since 1985 a professor of African Studies at the State University of New York, Stony Brook. He retired in 2000, but has continued read his poems in jazz sessions – as he has done 40 years. In 2001 Baraka visited Finland where read poems at a jazz evening with Hamiet Bluiett (saxophone), Wilber Morris (bass), and Reggie Nicholson (drums).

In the 1980s Baraka wrote two librettos, MONEY (1982, with G. Gruntz), and PRIMITIVE WORLD (1984, with D. Murray). His poems show an interest in music, and Baraka has also written many books on the subject (BLACK MUSIC in 1968, THE MUSIC: REFLECTIONS ON JAZZ AND BLUES in 1987). In his short story, ‘The Screamers’ in TALES (1967), Baraka dealt with the galvanizing force of black music upon a black audience. Poetry is music,” he has once said, “and nothing but music. Words with musical emphasis.” His large home shows signs of music and African culture everywhere: photographs of the author with the saxophonist John Coltrane, piano which was bought when the singer Nina Simone lived with the family for a few months, African sculptures, furniture, and textiles. In his youth Baraka practiced piano, trumpet and drums, but found that poetry was for him a more suitable form of expression.

Baraka continued to write in the 1990s while also teaching at SUNY-Stony Brook. He has edited many anthologies of African-American writing, and has been honored with numerous fellowships, grants, and awards. His political frankness has not become milder, as can be seen in GENERAL HAG’S SKEEZAG (published in Black Thunder, 1992). In 2002 Baraka’s ‘Somebody Blew Up America,’ a Sept. 11 memorial poem, was labelled anti-Semitic. Baraka claimed that the poem was misinterpreted. Much of Baraka’s writings have remained unpublished, or have been printed in small pamphlets. The strength of his work is in its originality and in the attempt to turn from a Western cultural background to a new black aesthetic, flowing from the alternative cultural movements of Africa and America.

Source: Books and Writers

Amiri Baraka Poems